Projects

Crustacean Genomics

Pancrustaceans are a group of arthropods that includes familiar animals like insects, crabs, and lobsters, as well as thousands of other species with extremely varied ways of life including mantis shrimp, 12-foot wide Japanese Spider Crabs, microscopic tantulocarids, shell-incased barnacles, giant deep-sea isopods, and many others. For centuries scientists have debated how these various animals evolved, and much of this still remains a mystery today. By using large genomic and transcriptomic datasets and expanded taxon sampling, I hope to better understand their evolution and resolve this large and important branch of the tree of life. We are particularly interested in collecting rare, unsampled groups of crustaceans that can break long branches and help better resolve the phylogeny. You can see some of the latest revisions and target taxa in our recent paper in Molecular Biology and Evolution

Parasitic Copepod Diversity & Systematics

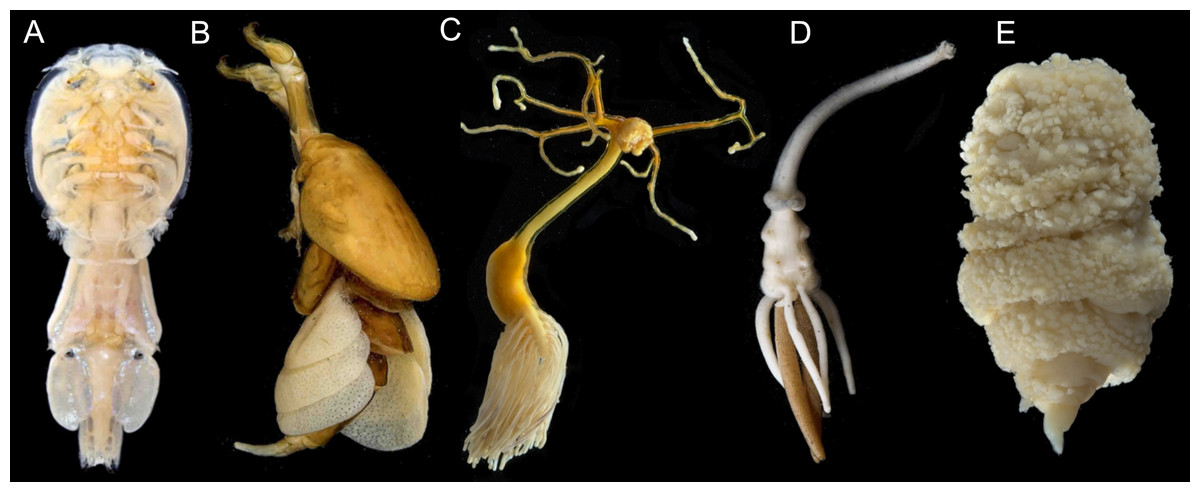

Copepods are a group of small aquatic crustaceans containing >14,000 species that are likely the most abundant animals in the ocean. Most copepods are about the size and shape of a sesame seed or grain of rice, but their small size belies their essential role in ecosystems. They are ubiquitous in aquatic environments from mountain streams to all depths of the ocean and are even abundant in canopy mosses and wet soils. Most ocean animals are directly or indirectly dependent on copepods as a food source. In addition, about half of all copepods (>6,000 species) are parasites of other animals – my research largely focuses on parasitic copepods.

I combine field expeditions, traditional morphological identification, advanced imaging technologies, and genomic analyses to better understand copepod diversity. I use light microscopy, microCT, SEM, and histology to identify copepods, describe new species, and document their morphology. I use next-generation sequencing (NGS) and phylogenetic analyses to understand how copepods are related to each other and how they have diversified. Much of the copepod tree of life remains largely unresolved, with only >4% of copepod species included in phylogenetic analyses. Despite this lack of resolution, current data suggest copepods evolved to be parasitic at least 14 times which has resulted in spectacular morphological diversity and extreme host range (14 phyla). Taken together, this makes the Copepoda an ideal system to test hypothesis regarding the evolution of parasitism, morphological evolution, and the evolutionary dynamics of host associations. My 3 year NSF postdoc research fellowship focuses on building the copepod tree of life by developing an UCE probe set for copepod phylogenomics.

Tapeworm Taxonomy and Systematics

Tapeworms are parasites that live in the intestines of vertebrates. They lack all elements of a digestive tract, instead they rely on their host for nutrients, which tapeworms absorb through the surfaces of their body. I have described 5 species of tapeworms from sharks and documented a novel attachment mechanism in a genus of shark tapeworms. While most tapeworms attach with their head, a specialized attachment organ called a scolex, species of Calliobothrium use, to a much greater extent, spikey structures along the length of their body to attach to the villi on the gut of their hosts.

Computational Biology

I apply computational biology methods to answer biological questions. Often, these questions are related to the topics above, but I have also collaborated in a variety of other areas including human gene expression in cancer, mouse models of human disease, microbiome characterization, and hookworm developmental gene expression. My computational biology work has involved phylogenetics, ortholog identification, transcriptomics, differential gene expression analysis, microbiome analysis, and genome annotation.